Woolf: ‘A Room of One 's Own ’

Virginia Woolf was one of the most important novelists of the Modernist period and a leading figure of the Bloomsbury group of writers, artists, and intellectuals in post-World War I London. She first wrote the extended essay that became A Room of One’s Own in 1928 as a pair of invited lectures to the students of Girton and Newnham, the women’s colleges of Cambridge University, on the theme of “Women and Fiction.” The text was then revised, expanded, and published the following year as this volume by Hogarth, the small but important press that Woolf owned and operated in London with her husband, Leonard.

The chapters included here—which at times read as an extended fictional narrative—address the social and material challenges faced by women writers historically. In chapter three, one of the most frequently reprinted sections, Woolf answers the question of why there have been no women writers equal to Shakespeare. She does this by imagining what would have become of a female, born in Shakespeare’s day, with Shakespeare’s genius. Owing to social conditions designed to squelch women’s public and literary voices along with their political and economic independence, “Judith Shakespeare,” as Woolf christens William’s invented sister, would have died young, poor, and pregnant. She concludes, “It would have been impossible, completely and entirely, for any woman to have written the plays of Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare.” Indeed, in the title essay, Woolf makes her famous and still influential argument that in order to write successfully,

Indeed, in the title essay, Woolf makes her famous and still influential argument that in order to write successfully, any woman of talent needs “£500 and a room of her own.” That is, she needs enough income to support herself with reasonable comfort and freedom of time and space away from the daily domestic duties and social expectations that consume the lives of most women.

Woolf’s slim volume has remained one of her most popular and influential books and is still widely read and taught today in college courses on literature and women’s studies, among other subjects. It has been adapted into a one-woman play and into a film by famed British actress Eileen Atkins.

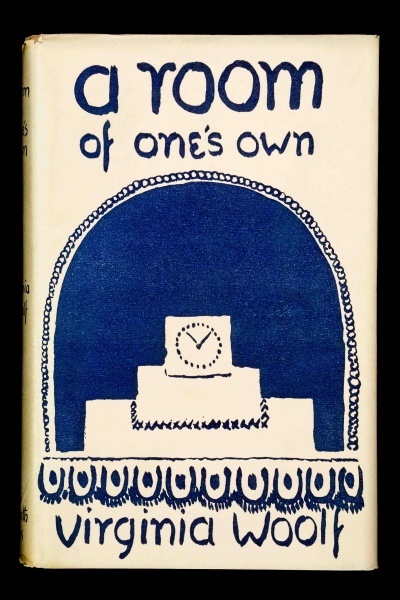

The first edition on display in Imprints and Impressions is especially interesting because of its provenance: It belonged to Woolf’s friend Helen Anrep, to whom the author had presented it herself, as the inscription, “Helen, from Virginia” indicates. Anrep was a lover and patron of the arts. She was first married to the Russian painter Boris Anrep but left him in 1924 for Roger Fry, the art critic and former paramour of Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell, whom Anrep met in Bloomsbury. Vanessa Bell created the cover art for this first edition. Thus, three women intertwined in a small and complex social and intellectual sphere, all born into class privilege, and all using their resources to reshape the modern world of arts and letters—Woolf, Bell, and Anrep—appear together in the physical matter of this book.

—Sheila Hassell Hughes, PhD, Professor, English

Excerpt from Virginia Woolf's "A Room of One's Own" read by Sheila Hassell Hughes, Professor. University of Dayton. Department of English