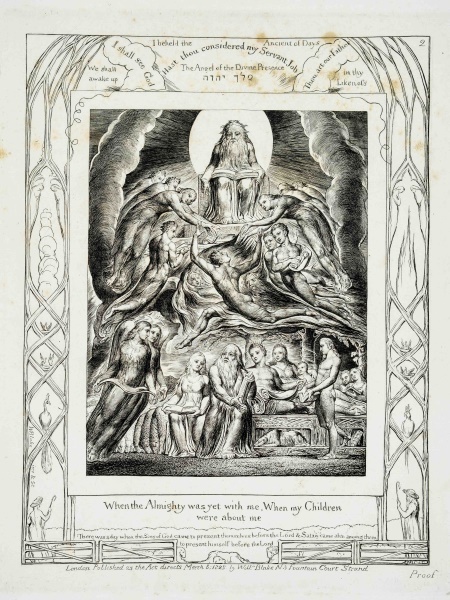

Blake: Illustrations of the Book of Job

It would be inaccurate to call William Blake’s contributions to the Book of Job just illustrations, although this is what the series of twenty-two prints is commonly called. Blake was known to integrate verse and visual art in his creations. The methods he used in the creation of his artworks were inventive. Scholars still debate the details of some of the actual techniques he employed. Unlike most artists, engravers, and authors of his day, he maintained hands-on control over every step in the production process of his book publication. For this book, he used verses from the King James Bible. The verses he used included excerpts from the Book of Job and verses from other biblical books. Blake tended to see and to create interesting juxtapositions of images and ideas in his works.

Blake was something of a Renaissance man two hundred years after the Renaissance. He was a poet, artist, engraver, and more. Blake’s background was rather humble. G.K. Chesterton wrote,

Like so many other great English artists and poets, he was born in London. Like so many other starry philosophers and naming mystics, he came out of a shop. His father was James Blake, a fairly prosperous hosier; and it is certainly remarkable to note how many imaginative men in our island have arisen in such an environment. Napoleon said that we English were a nation of shopkeepers; if he had pursued the problem a little further he might have discovered why we are a nation of poets.

Blake received his early education through homeschooling. He was intelligent and wellread. From an early age he claimed to see extraordinary visions. One early and often mentioned childhood vision was the sight of a tree full of angels. Similar visions would haunt him throughout his life and influence his work. As a child, he was apprenticed to the great master engraver, James Basire, who assigned him to draw monuments in Westminster Abbey. Scholars have traced themes in Blake’s engravings to this experience. He was particularly taken with the works of Albrecht Dürer, among others.

Blake married Catherine Boucher and taught her how to read and write. He also taught her the art of engraving. She was to become his partner in life and in business.

The Blake family struggled economically throughout their lives. William Blake was a progressive, perhaps revolutionary thinker. Although spiritual, he was critical of the English institutions of church and state. In his poem “London” from Songs of Experience, he wrote,

In every cry of every man In every infant’s cry of fear, In every voice, in every ban, The mind-forged manacles I hear: How the chimney-sweeper’s cry Every Blackening Church appalls, And the hapless soldier’s sigh Runs in blood down palace-walls.

Blake had an interesting circle of important progressive friends. His circle included Joseph Priestly, Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, and Richard Price. They were all interested in social justice and human rights. Priestly was a prominent scientist who was known for his work with gases. Paine was a revolutionary pamphleteer, author of “Common Sense” and “The Rights of Man.” Wollstonecraft was a philosopher and author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Godwin was a Utopian business owner. Price was a political and social philosopher. Although they were British subjects, each member of this community embraced both the American and French revolutions.

—William Marvin, MA, Lecturer, Philosophy

William Skelly, a graduate student in English, describes William Blake’s interest in blending verse and image as an exploration of the Biblical figure of Job. Interview is an online supplement to the University of Dayton exhibit Imprints and Impressions: Milestones in Human Progress—Highlights from the Rose Rare Book Collection, held Sept. 29 through Nov. 9, 2014.