Dostoevsky: ‘Brothers Karamazov’

In Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky brings together ethical and theological ideas foundational to his worldview and explored in earlier works such as Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Idiot (1868). Themes such as the psychological struggle between faith and reason, the distinction between human and divine justice, and the paradox of the existence of evil under the jurisdiction of a loving God obsess the author, and by extension, his characters.

Brothers Karamazov is a family drama, a crime novel, and a philosophical meditation that tells the story of four brothers and their neglectful father, Fyodor Karamazov. Fyodor, a self-professed buffoon, miser, and insatiable lecher, embodies unpunished evil.

“Why is such a man alive?” exclaims Dmitri, Fyodor’s eldest son. The question of why Fyodor continues to enjoy his depraved life in old age without divine retribution is personally significant to his sons. Twice a widower, Fyodor cruelly mistreated both of his wives and after each of their untimely deaths promptly forgot about his offspring, leaving them in the care of servants or distant relatives.

The attempt to make sense of a traumatic past leads each of the brothers on a different path. Ivan retreats into an “ivory tower” to ponder injustice from an intellectual distance; Dmitri loses himself in sensual pleasures; Alyosha, the youngest, seeks refuge in his faith and joins a monastery; the fourth son is illegitimate and does not carry the Karamazov name. His mother, a mentally ill homeless woman dubbed “Stinking Liza,” became pregnant after Fyodor drunkenly bet his friends that no woman was too repulsive for him to bed. Given the surname Smerdyakov (Stinker) after his mother’s insulting moniker, the unacknowledged son Pavel grows up to become a servant in his father’s house and remains a sycophantic follower without a distinct personality of his own.

As in Crime and Punishment, the complex plot of Brothers Karamazov revolves around a murder, which occurs early on in the novel. Each brother has a motive for killing his father, but the mystery surrounding the parricide remains even after the trial is over and the guilty party has confessed. The true responsibility for the crime extends beyond the physical act of murder to the murky territories of intention, conspiracy, and compliance. At the end of the work, the reader is left wondering what was the first link in the cause-and-effect chain that culminated in the death of Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov.

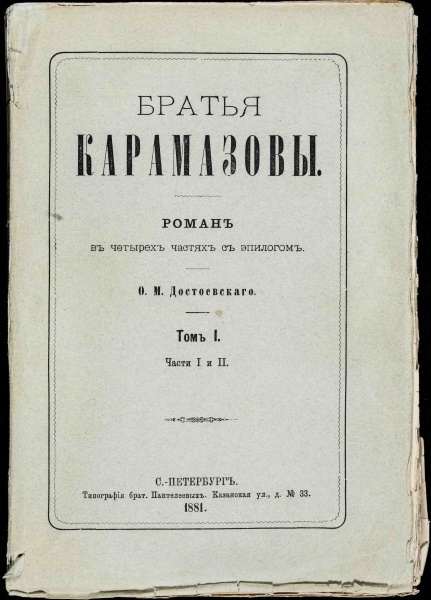

This is Dostoevsky’s longest and most famous novel and was originally serially published in sixteen installments in the journal The Russian Herald from January 1879 to December 1880. The first separate edition of the work appeared in 1880 in St. Petersburg. Dostoevsky died in January of 1881 before he had the chance to write the second part of the work, which he had planned to title The Life of a Great Sinner.

This text exerted enormous influence on the twentieth century’s seminal intellectual figures. Among the most famous fans of the novel were Sigmund Freud, whose 1928 article “Dostoevsky and Parricide” called Brothers Karamazov “the most magnificent novel ever written,” and Jean-Paul Sartre, who saw in Dostoevsky’s seminal work the beginnings of French existentialism.

—Masha Kisel, PhD, Instructor, English

Masha Kisel, an instructor in the English department, examines the relationship between faith and reason as seen in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov. Interview is an online supplement to the University of Dayton exhibit Imprints and Impressions: Milestones in Human Progress—Highlights from the Rose Rare Book Collection, held Sept. 29 through Nov. 9, 2014.