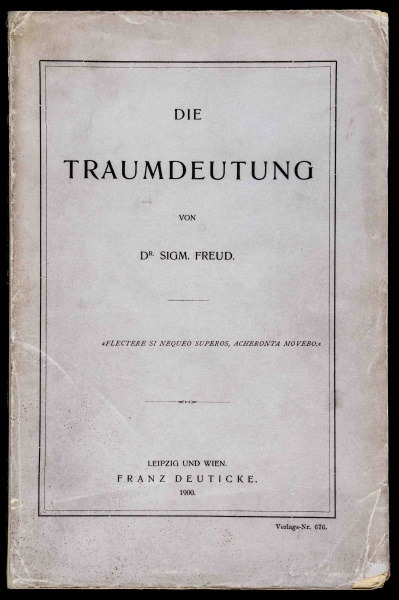

Freud: ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’

Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams has touched more people than would recognize themselves as having been touched by it.

Freud’s premise seems simple: Our lives mean more than we understand. We can recognize this insight from a range of perspectives. From a cosmic one, we can ask about what place we have in the universe, no matter how small that place might be.

From a theological point of view, we can grasp that our lives might mean something more than they appear because we are loved by our God. We can list ways to question the human place in the world, but before we begin to address questions about the general human condition, we first question our own inner lives and the conflicts we have between the inner world of our thoughts and feelings and the outer world of our relationships and behaviors.

Freud taught us that we could trace the things we do, the behaviors we control (and sometimes lose control of) to our most intimate and ancient wishes. Our behaviors are “symptoms,” in Freud’s terms, of our inner desires.

Similarly, our most ancient and intimate wishes—what Freud calls “unconscious”— animate our thoughts and ways of behaving. For Freud, our secret lives are often secret to ourselves. In listening to his patients, Freud was able to hear those secrets that the patients did not hear, and he was able to help them to see their own secret thoughts, feelings, desires, and motivations by looking at their dreams.

Freud was not the first to look at dreams, but he was among the first to take them seriously as one of the ways we think. By sitting with his patients and listening to them, he discovered that dreams have two structural pieces:

- the manifest content, or the dream narrative that we might tell a friend the morning after.

- the latent dream thought, or that which motivates the dream; it is what we ask about when we interpret the dream.

Dreaming is thinking. During the day, our thinking incorporates the feelings and desires that we have when we are able to control our desires and our thoughts. But at night, the mind seeks the satisfactions it could not get while awake.

The world of our dreams unfolds as a series of hallucinatory fragments. Even in the secret of our night, some wishes and desires are still too difficult for us to bear, so our minds, protecting us from our ancient wishes, alter those desires and translate the latent dream thought into what we report as our dream—the manifest dream content.

“The Dream book,” as Freud often called it in his letters, is the first major work of psychoanalysis. It laid the theoretical and practical foundation that continues to ground the daily work of psychoanalysts worldwide. The brilliance of the book is simple: It takes seriously what most people would ignore.

—Andrew Slade, PhD, Associate Professor, English

Andrew Slade, chair of the English department, explains the importance of Sigmund Freud’s exploration of dreams for the field of psychoanalysis. Interview is an online supplement to the University of Dayton exhibit Imprints and Impressions: Milestones in Human Progress—Highlights from the Rose Rare Book Collection, held Sept. 29 through Nov. 9, 2014.