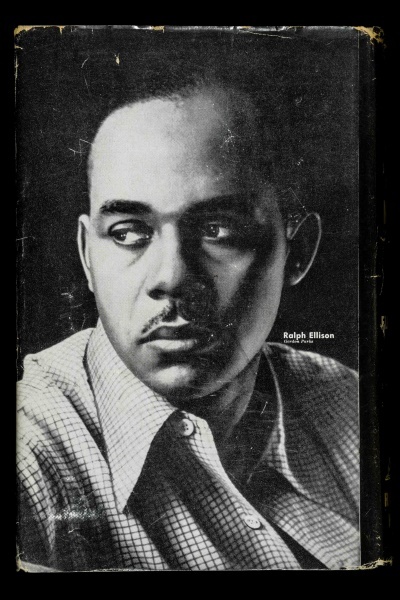

Ellison: ‘Invisible Man ’

To understand the structure and spirit of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, readers should understand something about that enduring AfricanAmerican musical form, the blues.

Despite dealing with often depressing subject matter—estrangement from a partner, family, or even oneself—ultimately the blues articulates a desire to transcend a desperate condition rather than dwell on its realities.

In his essay “Richard Wright’s Blues,” Ellison describes the blues as “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive.” Such a description should cast Invisible Man in a new light for readers who find Ellison’s novel to be dark or depressing. Reading Ellison’s novel resembles Ellison’s vision of the blues musician who, in transmuting sadness into art, employs the details of a brutal experience “to finger its jagged grain and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a neartragic, near-comic lyricism.”

Like the blues, Invisible Man is marked by a productive tension between the tragic and the comic. At times, the novel is unrelentingly bleak, as in the oftanthologized “battle royal” scene, in which black students fight each other for the amusement of whites and then retrieve coins from an electrified carpet. At the same time, several of the novel’s themes originated in jokes that circulated widely among twentieth-century African Americans, one of which is the very issue of invisibility alluded to in the novel’s title: the joke that some blacks were so black that they couldn’t be seen in the dark.

The experience of political and social invisibility was an unpleasant reality for many African Americans in post-Reconstruction America, but Ellison articulates that condition in an ironic and original literary voice.

Invisible Man is filled with surprising, almost surreal, episodes: early in the novel, the unnamed narrator receives a college scholarship, only to be labeled a “nobody” by the college’s president. Later, our protagonist lands a job in a Northern paint factory—one whose slogan is “Keep America Pure with Liberty Paints”—only to become immersed in the conflict between other black workers and white unionists. Near the end of the novel, the narrator again becomes disillusioned by his experiences with The Brotherhood—an organization that purports to aid the poor and marginalized but ultimately appears as exploitative as the institutions it claims to oppose.

The acclaim Invisible Man received surprised its author: Not only was the novel on the bestseller lists for sixteen weeks, but it received the National Book Award. However, the novel’s success stems from it being both local and universal.

Although clearly dealing with the plight of African Americans, in his own words, Ellison explores “the sheer rhetorical challenge involved in communicating across our barriers of race and religion, class, color, and region.” Despite its often pessimistic tone—after all, the narrator eventually retreats into an empty cellar to reflect on his disillusionment—Invisible Man offers an appeal to people to search for identity in a world that denies it to so many. After all, the narrator famously declares that “Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” Like the blues music that so inspired Ellison, Invisible Man has, for the past half-century, been speaking to and offering transcendence for readers adventurous enough to enter its darkly comic world.

—John McCombe, PhD, Professor, English

Excerpt from Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man" read by Herbert Martin, Professor Emeritus. University of Dayton. Department of English