Copernicus: On the Revolutions of Celestial Spheres

Why do we think about the cosmos? As Sherlock Holmes said, “What the deuce is it to me? You say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work.”

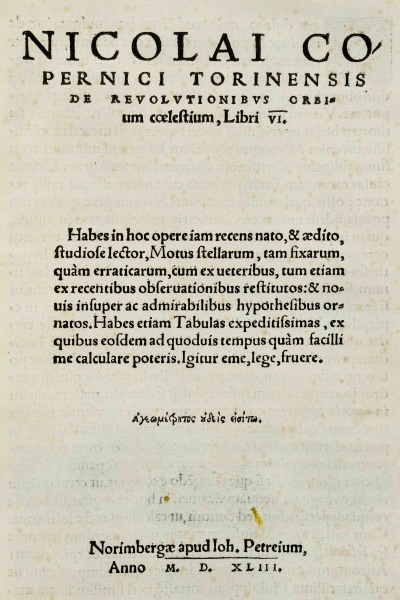

Clearly Copernicus (1473–1543), or those close to him, knew that there was a lot at stake. Finished very near the end of his life, De Revolutionibus was published posthumously with an introductory disclaimer that effectively said, “Here are some interesting ideas, but don’t take them too seriously.”

Copernicus himself was a widely versed astronomer, mathematician, and doctor of canon law and had been working on his heliocentric (sun-centered) theory of the solar system for at least two decades, but he had been hesitant to publish the full version.

In spite of this, the text had little direct influence and met mostly with silence, although it was read by both academic and theological audiences, as has been eloquently explored by Owen Gingerich in his work, The Book that Nobody Read. Although the work spent two centuries on the Church’s index of prohibited books, this was largely a result of the mood of the Counter-Reformation and scandals surrounding Galileo more than a halfcentury later.

Why was this work so intellectually dangerous? The basics of the cosmological background are well-known. The widely accepted (though not unanimous) view of the known cosmos, stemming most vociferously from Aristotle and delivered through Ptolemy and then the Scholastics, was that the earth is at the center of the universe (and a sphere, not flat). The sun and planets, as well as the fixed stars, revolved around this center point in perfectly circular orbits. At most, the system had become a bit unwieldy because matching theory to observations had required the addition of circular epicyclical orbits onto the main orbital paths.

Copernicus made a simple adjustment that rearranged the universe, or at least our understanding thereof. Now the earth was to be the third of the planets orbiting the sun, after Mercury and Venus and nearer than Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. On the other hand, it must be remarked that Copernicus’s theory also needed the artifice of epicycles and equants to make observations and theory agree.

In the end, some criticisms of the Copernican universe were not unfounded— his theory did not necessarily do a better job of making predictions and no physical reasons were given as to why an alternative to Aristotelian physics was necessary. It would not be until Johannes Kepler (elliptical orbits, ~1600), Galileo Galilei (telescope observations, ~1600), and Isaac Newton (theory of gravitation and laws of motion, ~1700) that heliocentrism would finally be justified and Copernicus vindicated.

We often think of this act of heavenly displacement as being problematic because it removed humans from the center of action and demoted God’s creatures to the status of inhabitants of one planet among many.However, an interesting interpretation that presents a very different but convincing view is that of Dennis Danielson, who contends that the problem was exactly the opposite. In medieval cosmology, the heavenly spheres belonged to an exalted region of perfect unchanging matter. This was why comets and supernovae, known from antiquity as irregularly appearing blemishes on the firmament, were such a challenge. By moving the earth, and humans, out to the celestial spheres, Copernicus was actually promoting us to a place we did not deserve.

One way or another, De Revolutionibus represents a crucial step in the ongoing process that is the science of cosmology. Although we no longer have the direct need for astronomical observations and theory to make calendars more accurate, the main reason for caring about geocentrism vs. heliocentrism or some other theory is that we as humans are curious about the natural world, a chief characteristic separating us from other creatures.

—Robert Brecha, PhD, Professor, Physics

Robert Brecha, professor of physics, explains Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric theory and the impact of his observations on early scientific inquiry. Interview is an online supplement to the University of Dayton exhibit Imprints and Impressions: Milestones in Human Progress—Highlights from the Rose Rare Book Collection, held Sept. 29 through Nov. 9, 2014.